Words, you find, are sometimes hard to find. This feeling I had needed structure, but my thoughts just twisted themselves into diving spirals, wound themselves out into nothing. I tried, and tried, to write it down, to make sense of it, but, while the feeling remained, the words just weren't there.

When I saw The Next Day, however, it all became clear.

To find context - to make sure I was right - I needed to go back. I started at the beginning - 1970, the first year of a decade in which David Bowie made a series of LP's, unrivalled since in either consistency or quality. Each record a masterpiece. Each song shaping scenes in teenage daydreams.

At this time, though, it wasn't the music that was important - just as it wasn't to be for The Next Day. That was not the conduit of this clarity. It was the album artwork - a great, lost language, all but forgotten in this digital age. A language Bowie spoke more fluently than anyone.

I lay them all before me:

The Man Who Sold The World (1970)

There'd been other Bowie records before this, but this was really the start of things. As with many of his records from this decade, the album cover artwork generated as much debate as the music it contained.

The original cover portrayed Bowie reclining on a chaise-lounge, resplendently attired in a 'man's dress', created by Mr Fish of London. It's difficult to appreciate the waves caused by Bowie's deliberate sexual ambiguity at the time, but such was the distaste for the cover photograph that RCA Records declined this artwork in preference for something much safer.

In the UK, the album was released in its familiar black and white cover, portraying a high-kicking Bowie.

In the US, the record appeared in a bizarre cartoon cover, before being replaced by the UK album artwork.

Hunky Dory (1971)

Bowie entered the Hunky Dory album photo-shoot clutching a book of Marlene Dietrich photographs. It's no suprise, then, that the album cover art features him in a pose reminiscent of the actress. Typically correct in his judgement, the cover photograph is a perfect metaphor for the visionary blend of gay camp, flashy rock guitar and saloon-piano balladry.

Numerous other photographs exist from the shoot, pictures of self-assured affectation, an androgonous being of impossible beauty.

The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars (1972)

On the evening of January 13th, 1972, Bowie and his band had just finished a photo-shoot with Brian Ward in a studio on London's Regent Street. At Ward's suggestion, Bowie was cajouled into extending the shoot outside, in Heddon Street, just off Regent Street. Altogether, 17 black and white photographs were taken, including those used for the colourised front and back cover of the album. 7 pictures were taken of Bowie posing in front of 23 Heddon Street, the site of furriers, K. West, 4 in and around the Heddon Street phone booth, and 6 close-ups of him in the doorway and under a streetlight.

The photograph chosen - Bowie stood on the steps of K. West, amongst discarded boxes and rubbish, was hand-coloured by Terry Pastor and would become one of the most celebrated album covers of all-time. It would also place Heddon Street on the map of London's most iconographic places.

On 27th March, 2012, the album cover was celebrated when a blue plaque was revealed, placed where the furrier's sign once hung, between two of the street's now numerous alfresco restaurants. It became London's second-only plaque to a fictional character, the other being displayed at 221b Baker Street, the home of Sherlock Holmes.

Aladdin Sane (1973)

After dropping the proposed album title, 'Love Aladdin Vein', partly because of its drug conotations, Bowie elaborated on the Ziggy myth with this follow-up album, the name of the record being a pun on 'A Lad Insane.'

Late British photographer, Brian Duffy shot the iconic Bowie portrait that features Ziggy Stardust in full make-up, a bold lightning bolt over one eye and a mysterious, clear liquid dripping from his clavicle.

It may be true to say that this image is, perhaps, the most famous in rock history.

Pin Ups (1973)

After name-checking 'Twig the Wonderkid' on 'Drive-In Saturday', Bowie met Twiggy and her manager, ex-boyfriend Justin de Villeneuve, socially a number of times and mentioned that he wanted to become the first man on the cover of Vogue. Villeneuve called Vogue and, using Twiggy as bait, managed to get them to agree to the idea of a photo-shoot.

Whilst Bowie was working on his album of cover versions, Twiggy and Villeneuve flew to Paris to make the shoot. Once set up, there was a moment of panic for Villeneuve as he realised that Bowie was pure white, whilst Twiggy was tanned from a recent holiday. Worried that the contrast would make the image look bizarre, the make-up artist suggested drawing masks on them both, and this seemed to work out better.

What happened next is in Villeneuve's own words:

I remember distinctly that I'd got it with the first shot. It was too good to be true. When I showed Bowie the test Polaroids, he asked if he could use it for the Pin Ups record sleeve. I said: "I don't think so, since this is for Vogue. How many albums do you think you will sell?" "A million," he replied. "This is your next album cover!" I said. When I got back to London and told Vogue, they never spoke to me again. Several weeks later, Twigs and I were driving along Sunset Boulevard and we passed a 60ft billboard of the picture. I knew I had made the right decision.

Diamond Dogs (1974)

The original cover artwork featured a stylised painting by Belgian artist, Guy Peelleart, representing Bowie as a freakish half-man, half-dog sideshow curiosity. RCA took immediate exception to the anatomically correct creature, withdrawing the record and ordering the artwork to be reproduced with the canine genitalia airbrushed out.

A small number of original unaltered versions survived and reportedly approach $10,000 in value.

Young Americans (1975)

In a radical change of musical direction, Bowie replaced the Ziggy/'1984'-influenced rock of Diamond Dogs with, '...the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey.' The outcome of this 'plastic soul' phase was Young Americans.

For the cover artwork, Bowie provisionally wanted to comission a Norman Rockwell painting, but he retracted the offer when informed that Rockwell needed at least six months to do the job. The cover's photo was eventually taken in Los Angeles on 30th August 1974 by Eric Stephen Jacobs. Bowie's apparent inspiration for the airbrushed art cover came directly from a copy of 'After Dark' magazine, which featured an image, also taken by Jacobs, of Bowie's then-choreographer, Toni Basil.

Station to Station (1976)

A transition album for Bowie, developing the funk and soul of Young Americans, whilst presenting a new direction towards synthesisers and electronic motorik rhythms that would culminate in his Berlin trilogy of LPs.With its blend of funk, Krautrock, romantic balladry and occultism, Station to Station was a colder, more detached and more paranoid record than its predecessor.

The full colour original sleeve, featuring a still from the film, 'The Man Who Fell To Earth', was rejected by Bowie in preference of a cropped, black and white version of the photograph, which more accurately represents the stark nature of the album's music.

Low (1977)

Leaving Los Angeles to escape a dependent preoccupation with Nietzsche, Aleister Crowley and cocaine, Bowie relocated to Berlin. It was here, in the shadow of the Wall, that he was to make his three finest albums. It is also true that the artwork for these three albums was visually stunning, amongst the most striking, and challenging, in modern music history.

Also featuring a still from 'The Man Who Fell To Earth', some suggest the cover to Low was a visual pun on Bowie's state of mind at the time (Low profile). Personally, I love Alfonso Coley's interpretation:

The release of this album cover in 1977 was another testament to the artistic adversity of David Bowie. The Low album presents a silent and eerie mystique. The collaboration of orange-fiery colors used in all facets of the album design has brought about a fantastic array of hues that most artists shy away from. This is one of the reasons that separate David Bowie from other rock-artists. It was a trial and error photographic medium that was used to promote David Bowie's implausible new wave album. In another light and retrospective turn-there are glimpses of Andy Warhol when the viewer is exposed to the stark dimension of this photograph. The bright futuristic neon background accentuates David Bowie's personality as a pioneer-breaking the mold of the unusual convention of modern times.

The omission of objects of any kind has added to the dominance of this album detail, and with the dominance of David Bowie's face precluding any falsehood of indifference, it is an utmost tribute to artistic simplicity and ingenious techniques. So, when you peer into this spaceman mystique-you may see the future of something fantastic and true.

In an amusing riposte, Nick Lowe's album that followed the release of Low aped the omission of a final 'e' in it's title. Lowe named his album 'Bowi'!

"Heroes" (1977)

His best album, "Heroes" also has Bowie's finest cover artwork. It is, indeed, no coincidence that this is the artwork that Bowie chose to defile with The Next Day.

Shot by Masayoshi Sukita, the bizarre, robotic portrait has prompted various theories regarding its inspiration.

It's widely assumed that Eric Heckel's 1917 painting 'Roquairol' was the main inspiration for the photograph's pose. (Certainly, the cover of Iggy Pop's Bowie-produced LP 'The Idiot', released in the same year, was based on this work.)

Bowie has also stated that Heckel's print 'Young Man' was an influence on him at the time.

It's also speculated that the work of Walter Gramatte could have been an influence on the shoot.

Also intriguing is the 1914 painting by Egon Schiele, 'Self Painting With Raised Arms' that the "Heroes" cover seems to closely replicate.

Whatever the influences on the cover, the unnerving image, along with the quotation marks of the album's title, have made the "Heroes" cover one of the most admired, thought-provoking and highly-debated record sleeves in the last 4 decades.

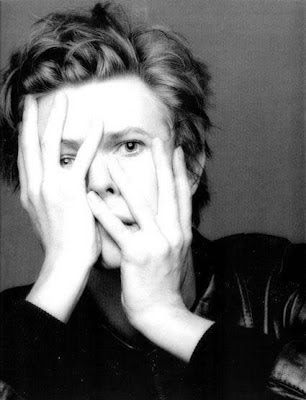

Shot in the same session by Sukita, the collection of discarded cover images feature Bowie expressing a variety of emotions, from serious, to pensive, to mischievous, to frightened. All are stunning.

Lodger (1979)

Lodger brought Bowie's decade to a conclusion. The spectacular fusion of songs it contains is mirrored by a cover that is equally confusing, dramatic, ugly and exquisite. It is, perhaps, my personal favourite.

Designed by Bowie, along with photographer Brian Duffy and artist Derek Boshier, the cover portrays a seemingly-falling Bowie, pressed, contorted and broken against an anonymous bathroom wall. It's an image that haunts me - a nod to the ways things might have been, a reminder that we're all, ultimately, lodgers in this world. Genius.

With the passing of the 1970's, Bowie would only make one more truely great album - 1980's Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Whilst Let's Dance was wildly popular, much of its content was insipid. His 80's output was sporadic and lacklustre, whilst the work he produced during the 90's was excellent in moments, but inconsistent.

By this time, I'd grown up. The importance of Bowie's new music had increasingly less emotional effect on me - it belonged to a different me. Once in a while, however, I'd only have to see the cover artwork of any of those 70's records and I'd be taken back to the time I discovered them - a time when these songs were, it seemed so painfully, everything I'd got to hold on to.

The emergence of a new song on Bowie's 66th birthday was both unexpected and spectacularly exciting. And whilst the song was good enough, it was the forthcoming album's cover artwork, and it's deconstruction by creator, Jonathon Barnbrook, that stopped me dead.

The Next Day (2013)

The Next Day takes something almost sacred, defiles it and makes it new. Like much great art, there'll be criticism that you could knock the final design together in 5 minutes. That's true, but it's also missing the point. Is it the finished result that is important, or the process of getting there?

David Bowie is, almost certainly, the first musician to take one of his own iconic album artworks and subvert it in this way. It's important. It's radical. It's breath-taking in both it's simplicity and impact.

Jonathon Barnbrook speaks most eloquently about his work:

We wanted to do something different with it – very difficult in an area where everything has been done before – but we dare to think this is something new. Normally using an image from the past means, ‘recycle’ or ‘greatest hits’ but here we are referring to the title The Next Day. The “Heroes” cover obscured by the white square is about the spirit of great pop or rock music which is ‘of the moment’, forgetting or obliterating the past.

However, we all know that this is never quite the case, no matter how much we try, we cannot break free from the past. When you are creative, it manifests itself in every way – it seeps out in every new mark you make (particularly in the case of an artist like Bowie). It always looms large and people will judge you always in relation to your history, no matter how much you try to escape it. The obscuring of an image from the past is also about the wider human condition; we move on relentlessly in our lives to the next day, leaving the past because we have no choice but to.

I know the reason why the cover of The Next Day has had such an effect on me. It's defined the feeling inside. .

A coming-to-terms with my own personal history, my own creative back catalogue of things fondly remembered and things best-forgotten.

The detachment I crave, and feel increasingly. From the suffocating grip of the past. From the headlock of the modern world.

All, and more, and more.

I've words now. I'll write them down.

Where I am. Where I'm going. The next day...

Very nice page! But you got the years of releases wrong for Young Americans, Station To Station and Low. SHould be 1975, 1976, 1977.

ReplyDeleteOf course...thanks Mikael

Delete